Childhood

Childhood is a time that may not be ordinarily associated with body art and decoration. In many African, Asian and Oceanic cultures, some cultural skin markings and ornaments are reserved until the first important juncture in life at puberty. In the UK, it is against the law for anyone to be tattooed under the age of 18, and in some other Western countries it is only permitted below that age with parental consent.

Usually the physical health and appearance of a child is the responsibility of the parent(s). In some cultures, this begins even before the child is born. An old Japanese superstition advises a pregnant woman against looking directly at a fire for fear of giving birth to a child with a red birthmark, nor should she attend a funeral for fear of causing a black birthmark. Fire also appears in traditional Filipino beliefs; a pregnant mother ought not blow on a fire or sit on a coconut for fear of bearing a child with a cleft lip and palate.Boys and girls are often obliged to appear as their parents choose or as demanded by society more generally. Although the effects may be subtler in children than in adults, it is often the case that the clothes, hairstyles and jewellery of children serve as distinctive markers of cultural, religious or social identity.

Boys and girls are often obliged to appear as their parents choose or as demanded by society more generally. Although the effects may be subtler in children than in adults, it is often the case that the clothes, hairstyles and jewellery of children serve as distinctive markers of cultural, religious or social identity. Girls and boys often only assume the right to wear particular body ornaments, clothes and colours, or make their own decisions about such things, when they reach puberty. Among the Suyá of Brazil it is not expected that children will behave very well or morally. It is only when the girls and boys reach the age where their lips or ears are pierced as a sign of adulthood that they are expected to listen to their elders and observe social regulations.

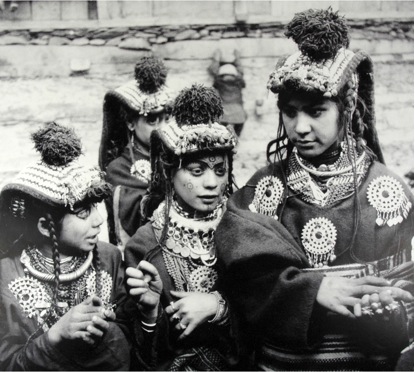

Young girls celebrating the Chaomos festival, Balanguru village, Pakistan. From a photograph taken by Peter Parkes in 1976The majority of special jewellery or clothing that may be put on children is done so as a protective measure against illness, danger or evil forces. Roman boys were given an amulet known as a bulla nine days after birth. Made of lead and covered in gold foil it was supposed to protect the boy from evil forces until he reached the age of sixteen and he could remove it. He would keep it however, and might wear it on important occasions, such as his promotion within the army, as a safeguard against negativity such as his own pride or the jealousy of other men. Girls wore a similar lunula (crescent-shaped) pendant from infancy until marriage.

Young girls celebrating the Chaomos festival, Balanguru village, Pakistan. From a photograph taken by Peter Parkes in 1976The majority of special jewellery or clothing that may be put on children is done so as a protective measure against illness, danger or evil forces. Roman boys were given an amulet known as a bulla nine days after birth. Made of lead and covered in gold foil it was supposed to protect the boy from evil forces until he reached the age of sixteen and he could remove it. He would keep it however, and might wear it on important occasions, such as his promotion within the army, as a safeguard against negativity such as his own pride or the jealousy of other men. Girls wore a similar lunula (crescent-shaped) pendant from infancy until marriage.

In Anglo-Saxon times, children learned spoken charms or doggerels by virtue of a jingle they carried around with them. These were similar to counting rhymes such as 'eeny meeny, miny moe' still used today.

In China, the colour red is considered lucky and is often used for children's clothes. Here, as in Myanmar (Burma), certain animals such as the tiger and elephant are also associated with special powers. In Myanmar, the hairs of an elephant's tail were traditionally made in to finger rings worn by a pregnant mother to stave away evil forces from her unborn child, especially if she had had other children who had died. The ring may have then been suspended as a pendant from the baby's neck after it had been born. Children under five would also wear charms around their neck carved from elephant nail or carved in the image of an elephant from wood or ivory. They might also wear pendants made of a tiger's tooth or the scales of a pangolin (anteater) to ward off sickness. Interestingly, the gold or brass discs decorated with the image of an animal, as worn by some Burmese children, has no protective function at all and are simply worn decoratively. Strings of small gold or metal pieces were sometimes around the ankles and wrists were worn in the hope that the child may grow up strong and healthy.